Everyone who knows me knows how much I love history. That love brought me to Crete, and here, I fell in love again — with the island, with my husband, and with something his family has treasured for generations: olive oil.

So it only feels natural to start my blog with this — the story of olive oil in Crete and Greece. From the very first wild olives to the traditions we still keep today, this is a journey through time, taste, and tradition.

The Ancient Roots - emphasizes the deep prehistoric origins

The olive tree has been growing in Greece long before humans were even here.

On the island of Evia, scientists found a fossilized olive leaf that is 23 million years old — proof that the olive tree is truly native to this land. Even more impressive, on Santorini, under layers of volcanic ash, they discovered more fossilized olive leaves from 50,000–60,000 years ago.

So before there were villages, temples, or olive presses, the tree was already part of the earth. What’s remarkable is that olive trees thrive on poor soil where little else will grow — this means land that would otherwise be barren can produce food, making them nature’s gift to survival.

The Minoan Legacy - highlights their pioneering role in Europe

The first people on Crete began collecting wild olives around 7000 BC. But the real transformation began around 3500 BCE when olives were first domesticated on the island. By the time of the Minoans — the first advanced civilization in Europe (3000–1100 BC) — olive oil was central to life, economy, and religion.

Inside the great Minoan palaces at Knossos, Phaistos, and Zakros, archaeologists found:

- Giant clay jars (pithoi) used to store olive oil

- Stone mortars and presses used for olive oil extraction that date back to 5000 BC

- Clay-spouted tubs used for separating oil and water following pressing, found at Early Minoan Myrtos around 4200 years ago

- Symbols for olives and oil in their writing systems (Linear A and B)

- Frescoes, pottery, and jewelry decorated with olive leaves

- Gold olive branches placed in tombs, showing the olive’s sacred status

What many don’t realize is that King Minos and his successors were the first patrons of the sacred olive tree, which played a key role in the economic prosperity of the Minoan civilization. Olive oil wasn’t just used locally — it became a major product for export, mainly to Egypt, making Crete one of the world’s first olive oil exporters.

Olive oil was used not only in food, but also for lamps, perfumes, medicine, and religious rituals. Some believe the olive tree was the holy tree of the Minoans, appearing in sacred ceremonies and offerings to the gods. Some of these olive oil presses are the oldest of their kind in Europe.

Even today, you can walk near these ancient ruins and find centuries-old trees still growing nearby — descendants of trees planted thousands of years ago.

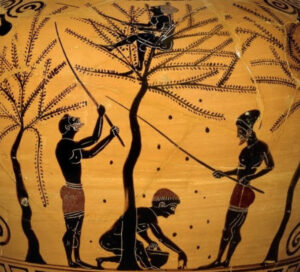

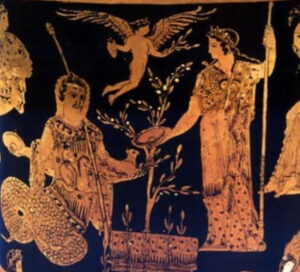

Classical Greece - connects mythology with Olympic traditions

As Greek culture expanded, so did the importance of the olive tree.

In mythology, the goddess Athena gave the first cultivated olive tree to the people of Athens. Her gift was chosen over Poseidon’s, and the city was named in her honor. That olive tree, they believed, stood on the Acropolis and was protected by the gods.

In daily life, olive oil was everywhere:

- Athletes rubbed it on their bodies before competitions like the Olympic Games

- Doctors used it in ancient medicine

- It was burned in oil lamps to light homes and temples

- It played a role in births, weddings, and funerals — from the first breath to the last

But here’s what made Greek olive oil truly special: The export of fine olive oil in the ancient Mediterranean can be equated with modern day trade in wine, with emphases on places of origin and varietals. Greece’s main exports were olive oil, wine, pottery, and metalwork, and during the Classical period when Athens reached the peak of its power, Greek olive oil was exported throughout the known world.

The importance of olive oil was so great that in the 6th century BC, Solon, the great Athenian legislator, drew up the first law to protect the olive tree with the exception of uncontrolled logging — one of history’s first environmental protection laws.

Olive oil became a symbol of purity, strength, and peace. It was celebrated in poetry, and even given as a prize to Olympic champions — not money, but a crown made of olive branches. A special type of vase, the Panathenaic prize amphora, was awarded to winners in the Panathenaic Games.

The Christian Era - captures the religious significance

When the Romans took over the Mediterranean, they understood the value of this liquid gold. The importance of olive oil as a commercial commodity increased after the Roman conquest of Egypt, Greece, and Asia Minor, which led to more trade along the Mediterranean. Olive trees were planted throughout the entire Mediterranean basin during the evolution of the Roman Republic and Empire. But Crete remained a key olive oil center.

During the Byzantine era (330–1453 AD), olive oil became more than food — it was a part of Christian faith and daily life.

- Oil lamps lit churches, homes, and streets

- Olive oil was used in baptisms and blessings

- Monks grew olives in their monastery groves, many of which still exist today

- Sacred oil, or chrism, was used in religious ceremonies

Many Byzantine monasteries in Crete still press their own oil the traditional way. Even today, when visiting, you might see ancient millstones and wooden presses still in use.

The olive tree, through all these centuries, remained sacred and alive — connecting people to God, to nature, and to each other.

Medieval Trade Routes - emphasizes the commercial expansion

From 1205 to 1669, Crete was ruled by the Venetians, who knew the value of olive oil. They encouraged its production and expanded olive groves across the island. Cretan oil became a major export to Venice and the rest of Europe.

They built large stone olive presses called fabrika, many of which still stand in villages today. Some even became the heart of local life, where families gathered to press their olives together during harvest season — a tradition that created the foundation for the cooperative spirit still alive in Cretan villages today.

Later, under Ottoman rule (1669–1898), olive oil continued to be a main part of both life and economy. Oil was used in cooking, soap-making, and even in taxation — people sometimes paid taxes with part of their oil harvest, showing just how valuable this liquid was considered.

Olive oil was traded far and wide, especially to Marseille, where it was used to make the famous Savon de Marseille soap. This connection between Crete and Marseille created one of the longest-lasting trade relationships in Mediterranean history.

Living History - beautiful contrast of ancient trees still producing

Crete is home to some of the oldest olive trees in the world.

The most famous is the Olive Tree of Vouves, believed to be over 2,500 years old — and it still produces olives today! Branches from this tree were used to crown Olympic champions in the 2004 Athens Games, connecting modern athletes to ancient traditions.

While the Koroneiki variety is the most well-known today, Crete is also home to ancient local varieties like:

- Tsounati – considered one of the oldest Greek cultivars, known since Minoan civilization, this hardy variety can be cultivated up to 1,000 meters above sea level and is mainly found in the Chania district. It can be picked late in the year, at the end of December or even beginning of January

- Chondrolia (also called Troumbolia) – the oldest and most distinguished olive tree variety from Crete, these larger olives are famous due to the natural way of fruit debittering and produce oil with hints of banana, nuts, tropical fruits, and aromatic herbs. Once a cornerstone of Cretan agriculture, Chondrolia is now endangered

Some of these trees are over 3,000 years old — older than many temples and cities — and still growing. What’s extraordinary is that these ancient trees often produce oil with flavors more complex and nuanced than younger trees, as if they’ve absorbed centuries of Mediterranean sunshine into their fruit.

Modern Crete - shows continuity with contemporary excellence

Today, Crete is known around the world for producing some of the finest extra virgin olive oil (EVOO). The island’s unique mix of sunshine, sea breeze, and mineral-rich soil creates the perfect terroir for olive trees.

Most Cretan families still own olive groves — often the same plots their ancestors worked centuries ago. During the harvest season (October to December), villages come alive with activity: hands picking olives, stone mills pressing the fruit, and the rich smell of fresh oil in the air.

Cretan EVOO is the heart of the Mediterranean diet, which is now protected by UNESCO as part of the world’s Intangible Cultural Heritage. It’s not just healthy — it’s a way of life that connects food, family, and tradition.

Modern producers mix traditional methods with new technology to keep the oil pure, sustainable, and full of flavor. Cold pressing within hours of harvest, temperature-controlled storage, and careful bottling ensure that every drop maintains the quality that made Cretan oil famous thousands of years ago.

And in many homes, including my husband’s, olive oil is still pressed the old way — with care, pride, and love passed down through generations.

A Taste of Time - poetic conclusion about experiencing history

In Crete, olive oil is not just something we use in cooking. It is a connection to the land, the ancestors, and the soul of the island.

When you taste real Cretan olive oil, you’re tasting:

- the wild leaves of Santorini preserved in volcanic ash

- the clay jars of Knossos filled by Minoan hands

- the sacred groves of Athena blessed by ancient priests

- the prayers of Byzantine monks echoing in monastery courtyards

- the hard work of generations who understood that some traditions are worth preserving

- the Mediterranean sun, sea breeze, and ancient soil that created this liquid gold

And maybe, like me, you’ll fall in love with it too — not just with the taste, but with the story it tells, the history it carries, and the connection it creates between past and present.